Unlock your child's hidden play patterns: Chris Athey's breakthrough schemas

Lines, circles, and boundaries in play become letters on the page. Discover how Chris Athey's schema patterns transform your child's physical explorations into the spatial understanding and motor control she'll need for writing.

Lines, circles, and boundaries in play become letters on the page. Discover how Chris Athey's schema patterns transform your child's physical explorations into the spatial understanding and motor control she'll need for writing.

Stand up and go to the door.

Open it.

Walk through it.

Now go to the kitchen and take a cup and fill it with water.

Now drink it.

You did the same thing three times.

It was a schema. Can you guess which one?

It's not trajectory or transporting, enclosing or enveloping. They're all close, but not quite right. So what's going on? None of the main schemas seem to fit.

That's because this is a new one, one identified by the brilliant British educational researcher, Chris Athey.

From outside to in, from inside to out, you - and the water - were going through a boundary.

Who was Chris Athey?

In the early 1970s, Athey led what would become known as the Froebel Early Education Project in London. Building on the foundational work of Jean Piaget, she took schema theory to new depths.

Her landmark book, "Extending Thought in Young Children: A Parent-Teacher Partnership" transformed how many of us understand children's seemingly repetitive play behaviours.

If you're a teacher, you must buy it. It's one of those rare educational texts that genuinely changes how you see children's learning.

But why should you, busy parent that you are, care about an educational researcher from the 1970s?

Because understanding Athey's insights might just change the way you see your child's play forever.

Beyond the basics: How Athey extended schema theory

Before Athey, the understanding of schemas was relatively simplistic. Most educators recognised a handful of patterns in children's play: transporting, connecting, rotating, and so on.

But Athey noticed something more profound happening.

She observed that children weren't just engaging with schemas through physical actions. They were representing these same patterns in their drawings, their language, their imagination, and their logical thinking.

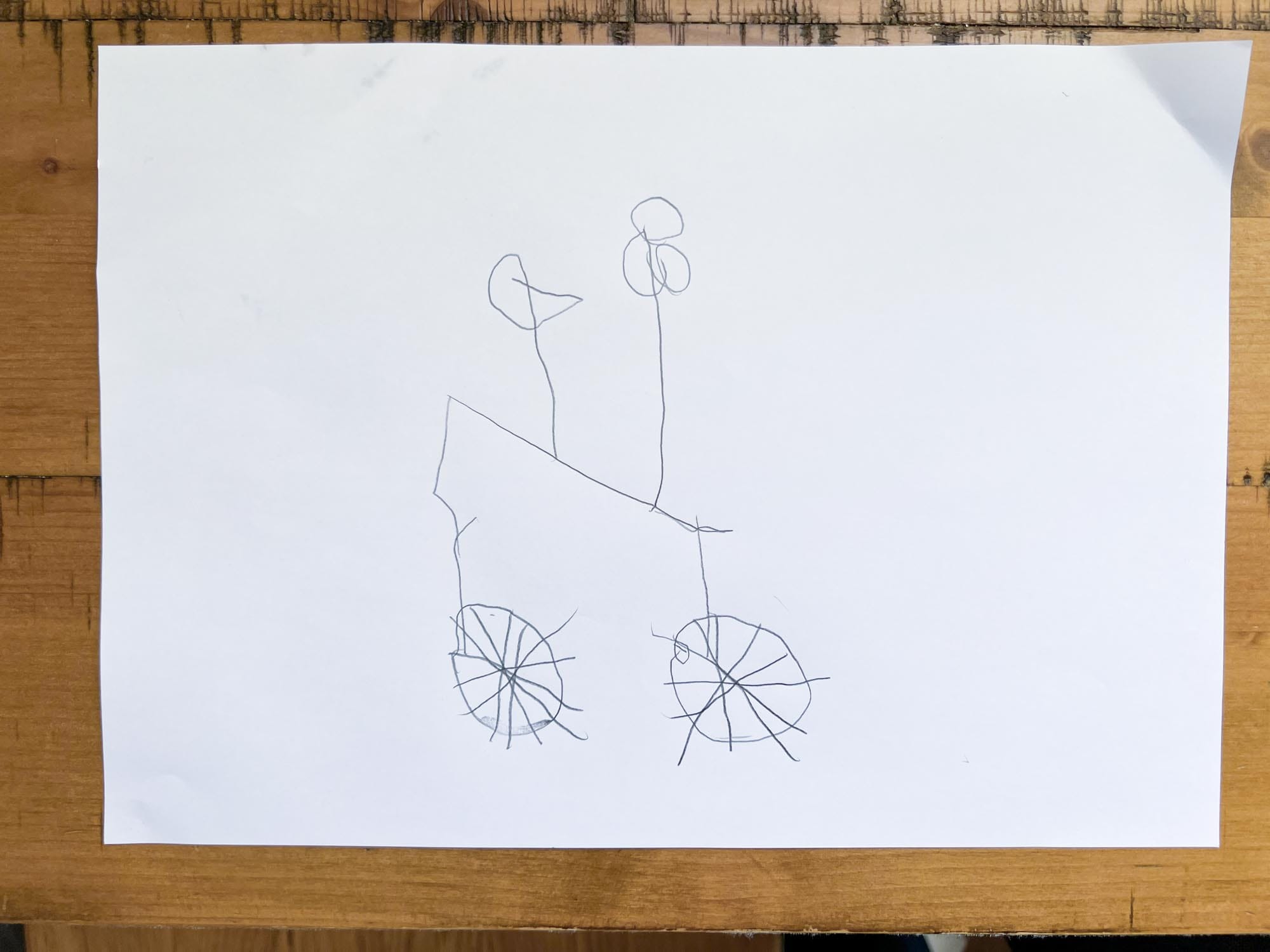

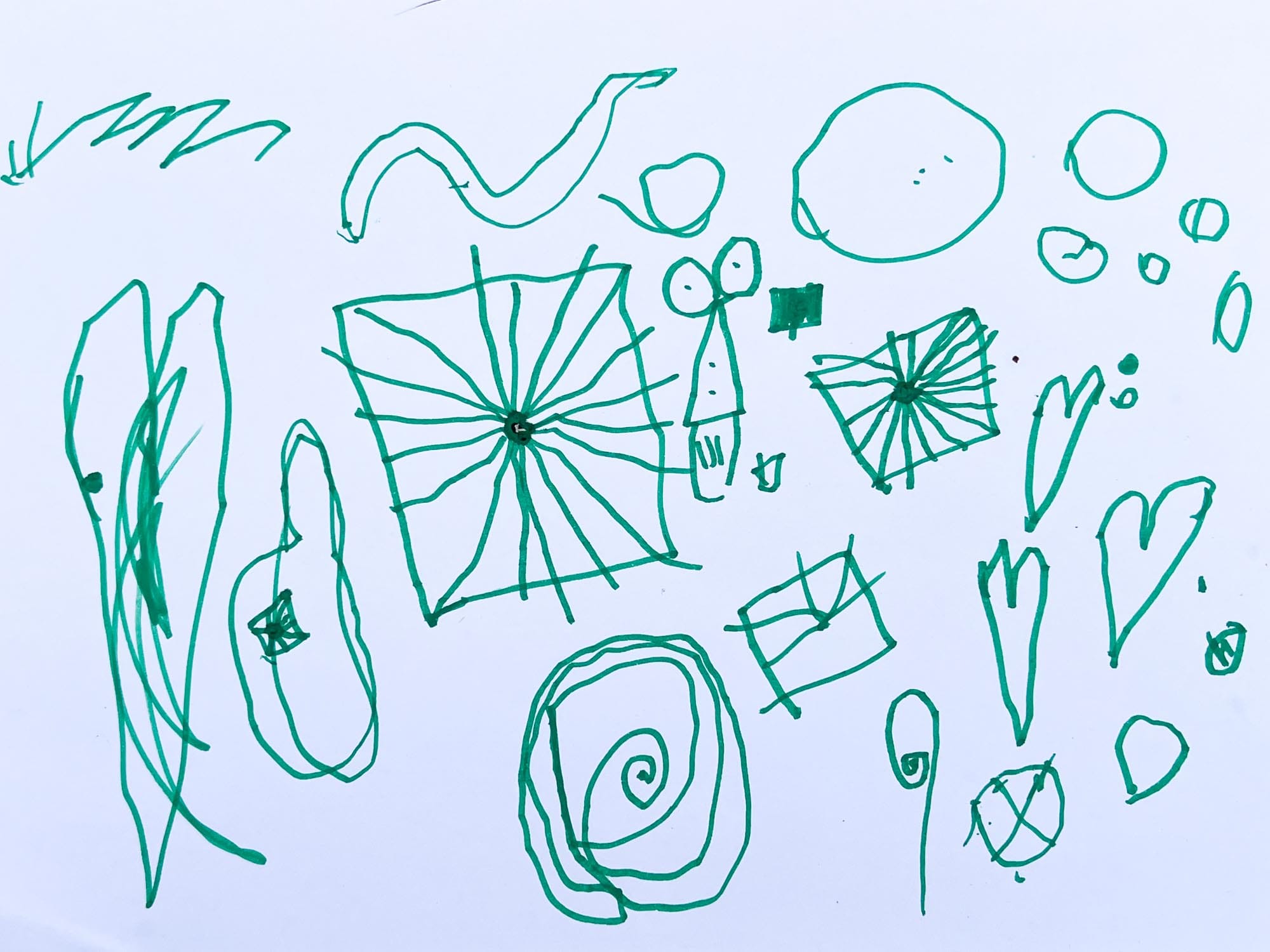

My daughter went through a phase of drawing nothing but circles with lines radiating out from them from suns to bicycle wheels. At the same time, she took delight in watching the sprinkler pulse intermittent jets of water across the lawn.

What Athey would help me understand is that these weren't separate interests - they were all expressions of what she called a core and radial schema - exploring how things move outward from a central point.

The four levels of schema development

One of Athey's most significant contributions was identifying how schemas develop through different levels of representation:

- Motor level: Physical actions and movements (twirling around, rolling balls)

- Symbolic level: Representing the schema through another medium (drawing spirals, pretending a ribbon is a tornado)

- Functional dependency level: Understanding cause and effect relationships (turning a tap makes water spiral down the drain)

- Thought level: Using the schema to think more abstractly (discussing how hurricanes form, or understanding the earth's orbit)

Watching my children move through these levels has been fascinating. What begins as a toddler endlessly dropping food from a highchair (motor level trajectory schema) eventually becomes a seven-year-old designing elaborate marble runs with precise calculations of angle and speed (thought level).

A schema spotting guide: Athey's breakthrough patterns

While most parents become familiar with common schemas like trajectory or connecting, Athey identified several sophisticated patterns that often go unrecognised. Here's how to spot them in your child's play:

Dynamic vertical schema

What to watch for: Your child repeatedly climbs up and jumps down, builds extremely tall towers, draws vertical lines up and down the page, or shows fascination with elevators, rockets, or anything that moves dramatically up or down.

Dynamic back and forth schema

What to watch for: She rocks on swings, enjoys pendulum movements, creates zigzag patterns in drawings, or moves toys back and forth repeatedly in a rhythmic way.

Dynamic circular schema

What to watch for: Beyond simple rotation, this involves creating intricate spirals in drawings, arranging objects in circular patterns, or moving her body in circular paths with increasing complexity.

Core and radial schema

What to watch for: She draws sunbursts or stars with lines radiating from a center point, arranges objects in radial patterns (like spokes on a wheel), or creates constructions where elements extend outward from a central hub.

Going through a boundary schema

What to watch for: She's fascinated by tunnels, doorways, and passages; enjoys games where objects pass through openings; draws objects penetrating boundaries; or creates play scenarios involving going in and out of enclosed spaces.

Going over, under and on top schema

What to watch for: She creates bridges in construction play, crawls under furniture, draws scenes with objects passing over others, or develops stories about characters climbing over obstacles.

Each of these patterns represents a distinct way your child explores and understands the world. Once you recognise them, you'll begin to see connections across different types of play that previously seemed unrelated.

What this means for you

Understanding Athey's breakthrough schemas isn't just academically interesting - it transforms how you can support your child's natural learning patterns:

- You'll spot meaningful patterns others miss. That zigzag drawing isn't random - it's your child exploring the dynamic back and forth schema that will later help her to colour in, form letters and develop fine motor control.

- You'll connect the dots between seemingly unrelated activities. When your daughter twirls in circles, then draws spirals, then arranges her toys in a circular pattern, you'll recognise the consistent schema being explored across different domains.

- You'll know when to step back. Rather than interrupting schema play as "repetitive" or "unproductive," you'll recognise it as valuable cognitive work.

- You'll provide more meaningful resources. Instead of random toys, you can offer materials that extend and challenge her current schema interests.

- You'll have more patience. When you understand the developmental importance of schema exploration, those moments of seemingly obsessive play become opportunities rather than frustrations.

My daughter's preschool teacher once commented, "She keeps drawing the same star pattern over and over - should we redirect her to try something new?" After I explained Athey's core and radial schema, the teacher began to see this repeated pattern as a strength rather than a limitation. She even provided materials for creating three-dimensional versions with craft sticks and clay, taking the exploration to a new level.

Supporting Athey's schemas at home

Athey's research shows that children's schema development follows a natural progression:

1. Physical exploration comes first

Before your child can represent ideas on paper, she needs to experience them with her whole body. Support her need to climb up and jump down, go through tunnels, move in spirals, or swing back and forth. These physical experiences create the bodily understanding that later translates to graphic representation.

Create opportunities for your child to:

- Move her body in all directions - up, down, across, through, around

- Experience what it means to be a straight line (running), a dotted line (hopping), or a curved path

- Feel the sensation of rotation, oscillation, and radial movement

2. Loose parts and construction play builds bridges

Once your child has physically experienced these patterns, she'll begin to recreate them with objects. Provide open-ended materials like:

- Blocks, sticks, and planks for creating boundaries to cross

- Materials for building bridges, tunnels, and pathways

- Items that can be arranged in radial patterns or circles

- Simple pendulums or balance toys

Watch how her constructions reflect her schema interests - toy trains going through tunnels, figurines climbing up and down structures, or blocks arranged in sunburst patterns.

3. Graphic representation emerges naturally

With a foundation of physical experience and object play, mark-making becomes meaningful. When your child draws vertical lines, zigzags, or spirals, she's not just scribbling - she's representing the schemas she's explored through movement and construction.

This progression explains why pushing children to practice letter formation too early often fails. The spatial reasoning and understanding of how lines connect must first be developed through whole-body experiences and hands-on play. When these foundations are in place, writing flows more naturally because the patterns make sense to the child.

Final word

The next time you feel frustrated by your child's seemingly repetitive play - the constant wrapping of objects, the endless lining up of toys, the persistent filling and emptying of containers - remember Chris Athey.

Your child isn't being difficult or lacking imagination. They're doing the complex cognitive work of building mental models that will serve them throughout life.

My son is now ten. The other day, I watched him carefully arrange his football cards, creating an elaborate classification system based on player statistics. I smiled, recognising the sophisticated evolution of the ordering schema that once had him lining up toy cars as a toddler.

Athey helped us understand that these patterns aren't random or meaningless - they're the foundations upon which all later learning is built.

So the next time you see your child engaged in schema play, perhaps instead of redirecting her to something "more productive," you might ask yourself: "What schema is she exploring, and how can I support it?"

Your patience and understanding might just be the greatest gift you can give to her developing mind.

Discover the secret world of schema play

Comments ()