The pattern I couldn't see

Why do children act the way they do? What drives them? A lesson I learnt during a tough start to my teaching career helped me become a better parent once it was time to have my own children.

On my first day of teaching, I thought I was ready.

Then I met the children.

As Mike Tyson famously said: Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face.

I don't remember ever being punched - though I did get a few kicks in the shin and the occasional pinch. But the biggest injury was to my pride.

I thought I knew what I was doing.

But at the end of that first day, I locked myself in the toilet and cried.

No, really. A 6'1" man reduced to tears by four-year-olds.

I didn't want to go back the next day.

It wasn't just that they were so unruly (it was a rough part of London, so I was prepared for the worst). It was that I knew I couldn't help them. I had a teaching qualification, but I felt like a fraud. I had no idea how to turn things round. I didn’t want to show up the next day - and I very nearly didn’t.

I wish I could tell you I had an epiphany right then and there. That everything clicked. But it didn’t.

I struggled for years. I got up early, stayed late, planned and replanned. I made special resources - bright, engaging, well-intentioned things I was sure the children would love. They ignored them.

It was demoralising.

And when I had children of my own, I went through it all again.

But this time, I was prepared.

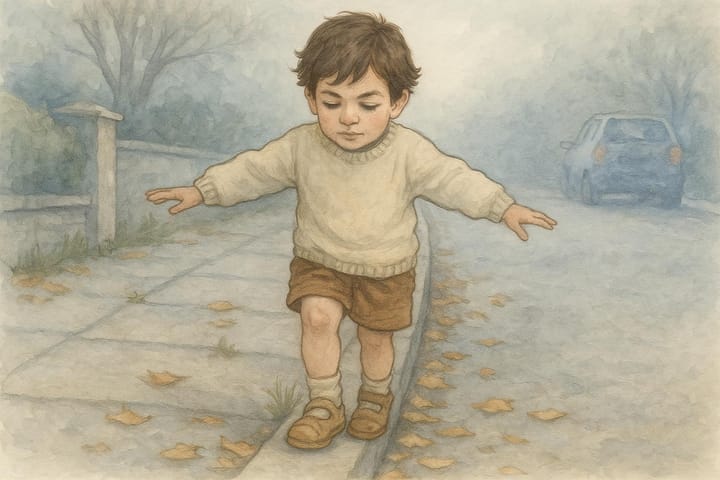

I'd heard about schemas before, during teacher training, but the idea had never really clicked. That changed one afternoon at a nearby nursery. I was observing a free-flow session when one of the assistants pointed to a boy outside, busily assembling ramps of various lengths.

"Jack is obsessed with the trajectory schema," she said. "He's out here all day."

That sentence changed everything.

Because suddenly, I could see.

Those repeated patterns of behaviour I’d noticed in the classroom? The ones I couldn’t explain? Now they had a logic. A shape. A name.

All of a sudden, I could categorise what I saw. I understood what it was about a pinwheel, the washing machine in the nursery kitchen, and Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush that fascinated one child but not another. One was exploring rotation. The other wasn’t.

Schemas gave me a new lens. They didn’t tell me everything, but they gave me a way in.

They helped me organise the space. I didn’t set up areas for each schema (that would have been impossible), but I made sure the nursery was full of open-ended materials that catered to a wide range of interests.

Trajectory might be a box of cars. Or the wooden railway. Or trikes in the playground.

I watched. I paid attention. If something was popular - if several children were deeply engaged - I’d add more opportunities to explore that schema.

And I started linking it all to the curriculum.

If we were learning about numbers, I’d write numbers on the front of each trike. I’d set up an old phone - or these days, a laptop - and invite children to place pretend pizza orders. The ‘delivery drivers’ would scoot around the playground, delivering pizzas to numbered playhouses.

Trajectory play (driving) met numeracy (matching numbers to house doors).

But the biggest change wasn’t to my provision. It was to my confidence.

Schemas helped me make sense of what I was seeing. They gave me clues. They gave me a reason why one activity might work for one child and not another.

And they reminded me of the most important thing I’d been taught during training: Start with the child.

Not the curriculum. Not the topic web. The child.

That’s why I’m building Patterns in Play - to help you do just that. Because once you understand what to look for, planning becomes so much easier. You can read more in Beyond the Textbook: The Schemas You Already Know.

You don’t need to memorise the official list of schemas. You don’t even need to name the one your child is exploring.

Just look for a type of play she keeps returning to. Then offer something else that seems to offer a similar challenge.

This is a hypothesis, of course. She might love playing with the washing machine and you, in triumph, declare: It’s the rotation schema! So you offer spinning tops and ride the roundabout at the playground.

A few disappointing trips to the park later, you realise your hypothesis was wrong.

What else could it be?

Maybe she’s fascinated by posting - putting things into the machine. Maybe she’s exploring enclosure, trying to understand object permanence by making things disappear. Or maybe she’s interested in boundaries: the moment when something moves from inside to outside.

In the end, it matters less what the schema is - or whether you guessed correctly - than what you offer your child in order to explore it.

The power of schemas lies not in classification, but in attention.

Schema play teaches you to look.

And once you start looking, you see all kinds of things. Not just schemas, but victories and defeats. Joy and sadness. Fine motor struggles. Superpowers you never knew she had.

You delight in her brilliance and uniqueness.

And best of all, you know your child better - and cherish her more.

Comments ()