The not-quite-schemas: Repetitive patterns that make sense of play

You've seen them before - the quiet rituals of childhood. The stacking. The scattering. The careful line of pebbles on a wall. These aren't random patterns - they're purposeful explorations. This guide helps you recognise what your child is really working on.

You've seen them before - the quiet rituals of childhood. The stacking. The scattering. The careful line of pebbles on a wall. These aren't random patterns - they're purposeful explorations. This guide helps you recognise what your child is really working on.

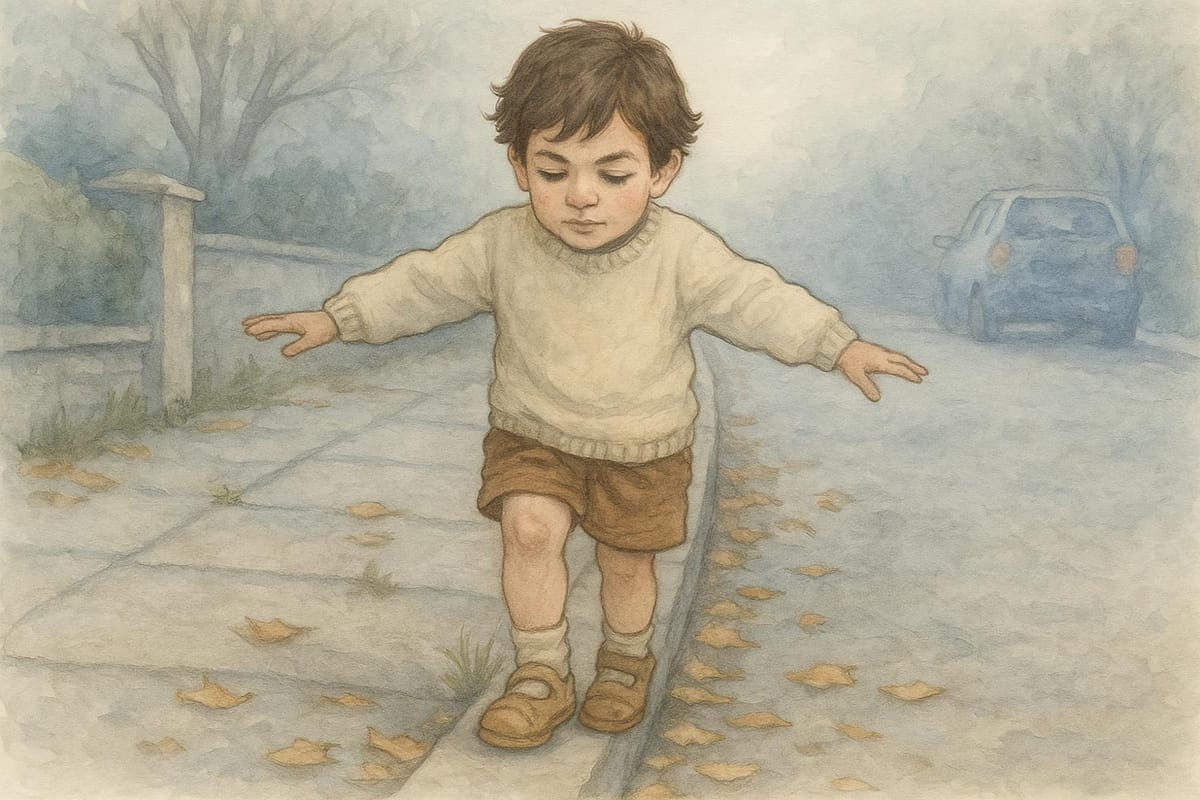

I'm two years old and I'm walking along the edge of the kerb.

My arms are out to the side and I'm wobbling. But I haven't fallen yet! I can still break my record.

Will I make it to the corner? I hope so.

All I really know is that this is fun.

The walking-along-the-edge-of-the-kerb schema hasn't made it into the textbooks but it's a good one. I've done it, you've done it and your child loves it.

There's something about walking a tightrope, kerb or painted line on the ground that's magnetic. We are all born with the urge to explore it, to master it.

But is it a schema? And does it matter?

Schemas are the invisible frameworks of understanding that your child builds through play. Think of them as mental maps that help make sense of how the world works. When your child repeats an action over and over - dropping spoons from a highchair, stacking blocks, or rolling cars down a ramp - she isn't just playing. She's a scientist, testing her ideas about what things are and how they behave.

Read more about schema play

The big schemas - the famous ones - are easy to spot. If your child is exploring trajectory, your home will be a mess of balls, trains and cars.

Other patterns are less obviously schemas.

Why focus on unofficial schemas?

We could call every repeated action a schema - and we'd probably be right. But with endless categories, the concept loses its power. These eleven patterns bridge the gap between formal theory and what we actually observe at home. They give you language for behaviours that might otherwise feel random or frustrating. When you can name the pattern, you can support it.

Why pay attention to these patterns?

This post introduces a collection of what we might call unofficial schemas - play patterns that are deeply familiar, but not always formally recognised in the literature.

These patterns give you a language for what you’re already noticing. They help you tune in more closely to your child’s inner world. Most importantly, they shift your perspective from seeing mess to seeing purpose.

When you notice these behaviours - and respond to them - you begin to understand your child on a deeper level. You can meet your child where she is. You can offer the materials she needs to go further, or step back when she needs space to explore.

For your child, this means more satisfying, purposeful play. For you, it means fewer battles, more confidence, and the quiet reassurance that she’s doing exactly what she needs to do.

1. Stacking schema

Stacking isn’t just about height. It’s about stability, intention, and trial and error. Whether your child is building towers with blocks or stacking biscuits on a plate, she is learning how to construct - and what causes things to collapse.

Overlaps with: Positioning, connecting

Try this:

- Offer blocks, tins, or cups of different sizes.

- Stack books or pillows together.

- Use stacking rings or bowls.

2. Scattering schema

To an adult, it looks like mess. But to a child, scattering is a kind of release. There’s joy in watching things fall, bounce, spread out and disappear. It’s a physical expression of space and movement - and a powerful way to learn about cause and effect.

Overlaps with: Trajectory, containment (inverse)

Try this:

- Set up a scattering tray with pom-poms, petals or rice.

- Let her throw leaves outside or scatter confetti.

- Use a parachute or scarf to bounce objects and watch them scatter.

3. Disconnecting schema

Pulling apart is as valuable as putting together. When your child dismantles a tower or takes a toy apart, she’s working out how components fit - and unfit. It’s controlled destruction, and it has its own logic.

Overlaps with: Connecting

Try this:

- Provide joinable toys like Lego or wooden train track.

- Invite her to disassemble simple household objects (e.g. battery-free torch).

- Offer Velcro fasteners or pop-beads to pull apart.

Honestly, if your child is anything like mine, she won't need any encouragement! The desire to destroy seems to be a feature baked into every child from birth...

4. Collecting schema

Many children go through a phase of needing to gather. Whether it’s all the red cars or a handful of pebbles, the collecting urge reveals a desire to group, to sort, and often to carry. There’s comfort in possession, and purpose in selection.

Overlaps with: Transporting, enclosing

Try this:

- Offer a handbag, bucket or small backpack and let her collect.

- Create a treasure hunt.

- Group natural objects by size or colour.

5. Lining-up schema

There’s something deeply satisfying about a neat row. When your child lines up her toys, she may be exploring pattern, order, or simply the pleasure of straightness. It’s a way of bringing visual harmony to a chaotic world.

Overlaps with: Positioning, ordering

Try this:

- Provide small objects she can sort and line up.

- Use masking tape to make lines on the floor to follow.

- Older children will enjoy story-sequencing cards, like eeBoo's Tell Me a Story series.

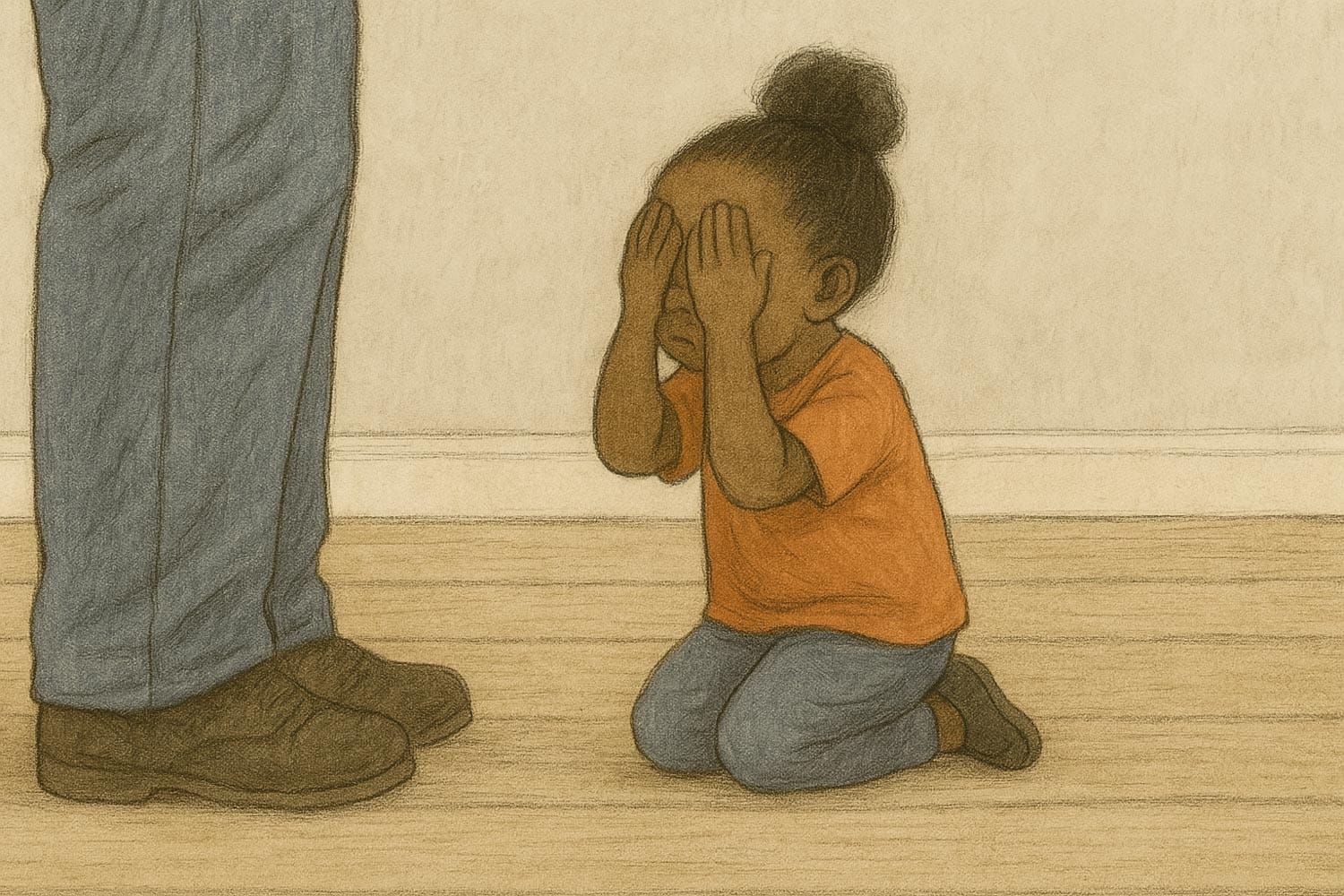

6. Hiding schema

Have you ever played hide and seek with a toddler? They 'hide' by covering their eyes with their hands...

They can't see you so you can't see them.

What simpletons!

In fairness to them and their rapidly-growing brains, there's a lot to master before you can play this game properly, from the trajectory schema to spatial reasoning, theory of mind and perspective. No wonder they succumb to magical thinking from time to time.

Babies crave closeness to their caregiver. Games of peekaboo help her endure short separations and prepare her for longer absences once she is mobile. This experimentation with object permanence and the understanding that the adult will always come back naturally creates a secure attachment bond.

Hiding takes this a step further. The separation is longer and the reunion is not guaranteed.

If your child is anxious, let her be the one who hides. If the tension gets too much, she is free to reveal herself whenever she likes. The problems arise when you hide: after a while she starts to worry that she might never find you - and that's a scary place to be when you're little.

My youngest is two and we're playing hide and seek.

...8, 9, 10! Here I come, ready or not!.

Where is she? Is she behind the sofa? Is she under the chair...?

I'm searching the room. I know where she's hiding - I can see her feet sticking out. But I'm taking my time. A little tension makes it more exciting.

Now she's starting to twitch. It's not fun anymore. She wants to be reunited with me - it's lonely back there - but she also wants to bask in the glory of her victory.

It's time to hurry me up.

Is she under the table?

No! a small voice calls out.

Is she in the box?

No!

I'm at the curtains. The game is reaching its climax

Is she behind the curtain?

Nothing. Not a sound.

I've found you! I know you're in there!

The fabric moves as she trembles with excitement.

With a confident tug, I sweep the curtain back!

I look right past her, a confused expression on my face.

Where is she? She's gone! I'm sure I heard her voice.

In this moment, her face is a picture.

Maybe I'm not there? you can see her thinking. Maybe I really have disappeared?

Sometimes I push it a little too far with my children. It's a character flaw. I can't help it.

I look behind the curtain from the other side.

She must be here! That's so odd. Has she vanished?

Vanished? Now she's getting worried. What if I never reappear?

The bottom lip is about to quiver.

Oh, there you are! How did you do that? You're so good at hiding.

You can see the relief on her face!

Phew! I'm back! she thinks. Maybe I'm just too good at hiding.

And then she's off to tell the others about her glittering success.

7. Balancing schema

From walking along a log to carefully placing a toy where it just holds, balancing is a full - body engagement with stability. It demands focus, coordination, and the courage to try again after wobbling.

Overlaps with: Rotation (vestibular), positioning

Try this:

- Use balance beams or masking tape lines.

- Stack objects in unstable ways and see what holds.

- Carry plastic cups of water on a tray to other family members.

- Enjoy an egg-and-spoon race in the garden.

8. Obliterating schema

Sometimes destruction isn't precise - it's total. Obliterating is about making things disappear completely: stamping muddy puddles until they're gone, rubbing out drawings entirely, or methodically dissolving sugar cubes in water until nothing remains. It's not about taking apart or breaking - it's about erasure, transformation, and the fascinating process of making something become nothing.

Overlaps with: Transformation, dissolving

Try this:

- Provide materials that dissolve or disappear (sugar in water, salt in warm water, ice cubes)

- Set up finger painting where she can completely cover and obliterate previous marks

- Offer chalk on dark paper where she can rub it away completely

- Let her stamp through muddy puddles until they're flattened and absorbed

This captures the complete erasure aspect that's different from both disconnecting (taking apart systematically) and destroying (breaking with force). The obliterating schema is about the satisfying process of making things vanish entirely.

9. Filling/emptying schema

Full. Empty. Again. Children are drawn to the satisfying contrast of containers being filled and then cleared out. It’s not just about stuff - it’s about volume, weight, and expectation.

Overlaps with: Containing, transporting

Try this:

- Provide cups and containers for water, rice or pasta.

- Use bottles with wide necks to fill and pour.

- Set up a mini sandpit or pouring station.

10. Pressing schema

There’s a particular joy in pressing things. Buttons, stickers, playdough - it gives immediate feedback. Pressing is about control and precision, but also satisfaction.

Overlaps with: Connecting, transforming

Try this:

- Use push-button toys or old remote controls.

- Play with stickers or (child-safe!) drawing pins.

- Offer dough, clay, or bubble wrap to press.

All four of my children loved playdough but the youngest had a fascination that continues to this day. Quite unbelievably, even today, aged 7, she still loves to press her fingers slowly into dough, watching the shape form and enjoying the slight resistance and springing back when she withdraws.

11. Draping schema

What happens when we cover something up? Draping fabric over furniture, hanging cloth over toys - these are explorations of enclosure and enveloping, space and transformation.

Overlaps with: Enveloping, containing

Try this:

- Offer scarves, muslins or play silks.

- Build dens with sheets and pegs.

- Let her hang things from furniture or string.

Conclusion

You don’t need to memorise every schema. You don’t even need to get the name right. The point is to pay attention. To spot the pattern. To say: “She keeps doing this. What is she working on?”

Schemas - official or unofficial - are clues. They help you understand the questions your child is trying to answer through play. And when you know the question, it’s easier to offer the right materials or give her the space she needs.

The next time she tips out the toy basket or spends ten minutes placing things in a line, pause before stepping in. She’s not being difficult. She’s learning.

Which one sounds like your child?

Comments ()