Introducing Patterns in Play

Do you love schemas?

I love schemas.

They’re the reason for my interest in child development.

If you aren’t familiar with them, I’d love to introduce you.

First, I was just a teacher. And quite an unhappy one.

I knew what to teach: the curriculum. I knew how to teach: the pedagogy. My worries came from not knowing the why.

At university, we were told to give children open-ended materials. Every preschool classroom should have a sand pit and a water table. We needed loose parts and pencils, puzzles and playdough.

But why? It really bothered me.

The myth of activities

My early years in teaching were spent searching for activities - frantically looking for something that would engage the children. Sometimes things worked, sometimes they didn’t. And without understanding why some activities succeeded while others failed, I felt like I was always starting from scratch.

When you don’t have a theoretical underpinning to your work, you are condemned to try and try again, never reaching your goal.

I was lost. What was I doing wrong?

The breakthrough

One day, I came across a book: Extending Thought in Young Children, by Chris Athey.

It’s hard going, but fascinating. And everything fell into place.

Athey took Piaget’s ideas about schemas and developed them. I’d heard about schemas before but it was only when I read this book that I understood the direct line between actions and thought. All of a sudden I saw the connection between a baby on her back, reaching for the mobile overhead, and the child writing putting words on a page.

In that moment, I realised that activities didn’t matter. You had to start with the child. Watch what she is doing. Notice the objects she finds interesting and the actions she repeats.

There are no activities, only children.

This is what the companion newsletter, Start with the Child is all about. The name says it all.

So why create Patterns in Play?

If I’m honest, it’s because I love schemas. They have a special place in my heart.

They are such an enlightening way to understand children’s play that they deserve - and can fill - their own newsletter.

What’s so satisfying about schemas is that you can see them, once you know how to look.

And once you see them, you know how to help. You don’t need to trawl the web for activities. You don’t have to ask your child’s preschool teacher for help.

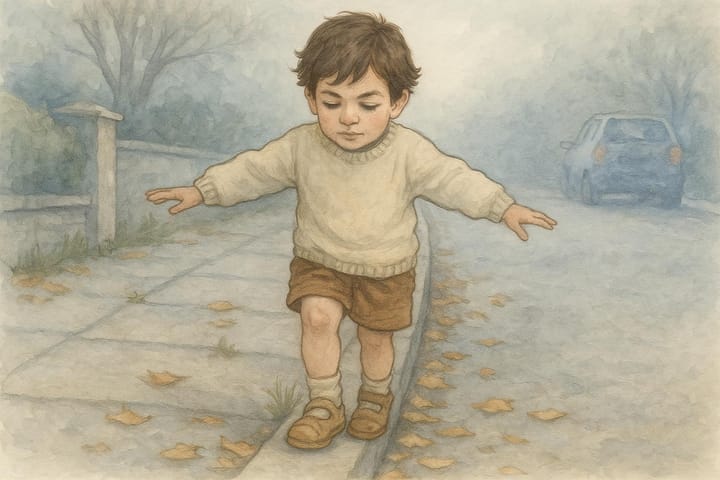

If your son loves watching the washing machine go round, delights in the roundabout and won’t be separated from his pinwheel, there’s a good chance he’s exploring the idea of rotation. Just find more things that go round.

The more you think about it, the more you realise that there are all kinds of different ways things can rotate. You can spin on the spot or you can spin a spinner. But rotation is also related to circular movements. You can dance around a friend or run around a track.

How about twirling a streamer, anti-clockwise?

Now do it with a pencil in your hand and you have the movement you need to make an ‘o’. And a ‘c’ and a ‘g’ and a whole family of other letters.

From washing machines to writing. What a journey! But, like Theseus in the labyrinth, once you pick up the thread, you can follow it all the way to the end.

Unlocking the patterns behind play

In Patterns in Play, you’ll discover that these seemingly small, repetitive actions are how your child builds her understanding of the world. And once you learn to decode these patterns, you’ll know exactly how to support her development.

We’ll explore the nuances of these schemas and how they evolve over time. You’ll understand not only how these patterns work, but also how they lay the foundation for more complex thinking and even symbolic thought.

You’ll never have to trawl the web for activities again.

Comments ()