Fine motor mastery

Forget what you've seen on Pinterest, fine motor control is not about tracing letters in sand and picking up pom poms with tongs. Your child craves meaningful activities to develop real-world skills. Better for her; easier for you. What's not to like?

Forget what you've seen on Pinterest, fine motor control is not about tracing letters in sand and picking up pom poms with tongs. Your child craves meaningful activities to develop real-world skills. Better for her; easier for you. What's not to like?

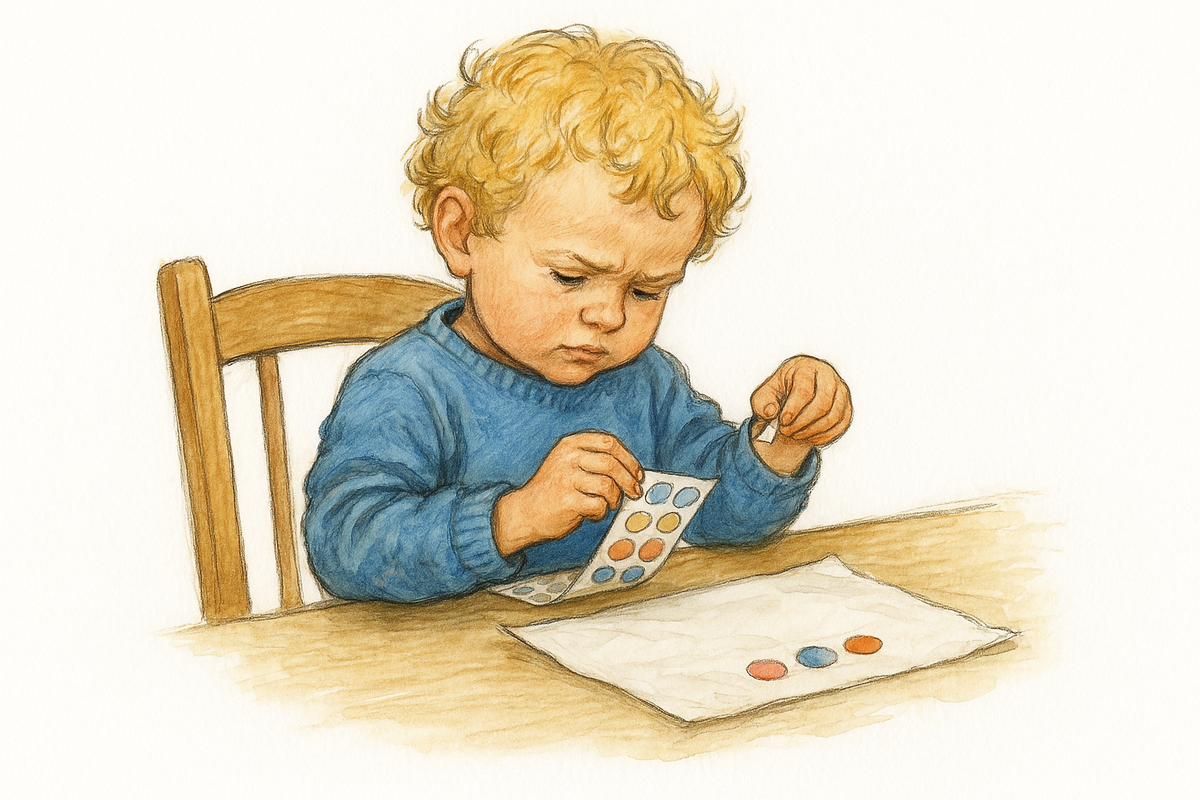

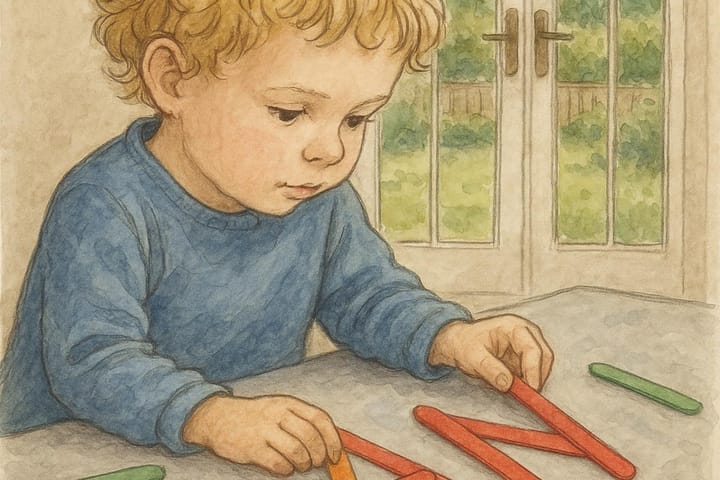

Sam's trying to peel a sticker off its backing sheet.

He's using both hands - one to hold the sheet still, the other to pick at the corner. It keeps folding in on itself. He frowns in concentration.

Then, suddenly, success!

The sticker lifts cleanly away from the paper. But now he faces a new challenge: how to get it off his fingers and onto the page where he wants it.

The first attempt goes badly - it sticks to his thumb instead of the paper. A brief cry of frustration, a vigorous shake of his hand, and he's ready to try again.

This time, he presses it down carefully with his fingertip, smoothing out the edges with deliberate precision.

"That was hard," he announces, looking up at his father with satisfaction.

And it was. But it was also a great workout for his developing brain and hands - the kind of challenge that builds the foundations for everything from tying shoelaces to writing his name.

What we get wrong about fine motor skills

As parents, we often think fine motor development is about handwriting practice: worksheets, pencil grip and getting ready for school.

Writing is important, but it's the crowning achievement. What we often miss is the long procession of foundational skills that comes before that are no less important and equally tricky to master.

Here's what parenting advice rarely tells you: your child doesn't need fine motor "activities." She needs opportunities to use her hands purposefully, solving real problems that matter to her. When your child is in velcro but is desperate to buckle her shoes because all her friends can, she'll practice more, persist more, and pay attention when you explain.

Now imagine giving her a box full of old shoes and saying, "Can you do up these buckles?"

It's not going to work.

What exactly are fine motor skills?

Fine motor skills are the small, precise movements of hands and fingers. They're what help your child zip up her coat, open a snack box, squeeze just the right amount of toothpaste onto her brush, or thread a bead onto string. But they're not one skill - they're dozens of interconnected abilities working together - and that means we'll need to offer a range of experiences.

The building blocks of fine motor development

Grasping

- Whole-hand grasp - Remember putting out your finger for your baby to hold? That's her whole-hand grasp. It starts out as a reflex - a strong one, too! You're probably a much nicer person than I am so I'm sure you didn't do this but I used to enjoy watching my children pick something up and then be unable to drop it again... There's nothing like watching a baby wave her arm in frustration, trying - and failing - to shake a rattle free from her hand. Who needs Netflix when you can watch your child learning to override the palmar reflex?

- Pincer grip - Once you can open and close all your fingers together, the next step is to focus on just the forefinger and thumb. This develops around 9-12 months and is crucial for so many later skills.

In-hand manipulation. You have something in your hand, but it's in the wrong part. How do you move it? There are three ways:

- Translation (from palm to fingertips) - It's the good old days and you're at a vending machine. You reach into your pocket and pull out some coins. Opening your hand, you look for the right coin and push it to your finger tips using your thumb. Holding it tightly with your finger and thumb, you close your hand, safely returning the remaining coins to your palm. You're ready to post the coin into the slot.

- Shift (adjusting grip) - Your child grabs a crayon but the grip is wrong. Carefully, she shifts her fingers until she holds it correctly. Get good at this and she'll soon be doing up the buttons of her shirt.

- Rotation (rolling with fingertips) - When your child rolls a crayon between her fingers or tries to open a bottle.

Bilateral coordination. Two hands working together. One holds the paper while the other draws. One holds the paper while the other cuts. One opens the button hole while the other pushes through the button. Like patting your head and rubbing your tummy, it's a lot to think about.

Hand-eye coordination. Want to catch a ball, draw a picture or thread some beads? Your eyes have as much work to do as your hands.

Dexterity. Fine motor skills are important but they're only useful if you can perform them quickly and efficiently. That's dexterity.

Strength and endurance. Congratulations, you can do up a button. But do you have the strength to do up the whole shirt?

Wrist extension. Lay your hand flat on the table, palm down, and lift it. That's wrist extension, a prerequisite for the tripod grip and happy handwriting.

Sensory processing and feedback. This secret fine motor 'skill' gives you the ability to adjust what you're doing in response to changing conditions. The writing paper is too slippery? You naturally slow down to avoid a messy scrawl. Your eyes didn't tell you this, your fingers did.

Phew! See? I told you there were a lot!

Threading beads just won't cut it. We need a plan.

Research spotlight: The grip development timeline

Children develop specific grip patterns in predictable stages. The tripod grip(thumb, index, and middle finger controlling the pencil) typically emerges between ages 3-4, but many children don't master it until age 6. The pincer grip (thumb and index finger) develops much earlier, around 9-12 months, and is the foundation for most later fine motor skills. Finger isolation - the ability to move individual fingers independently - develops gradually and is still maturing at age 5-6.

Meaning matters: why authentic work trumps Pinterest activities

Here's a nice Montessori activity.

A button frame. It's designed to simplify the tricky task of doing up fasteners.

It's a laudable aim.

But it's not real.

Real is quickly doing up your coat because it's snowing and you want to get outside. It's making party food for your birthday in the kitchen rather than putting jam on bread for a "teddy bears' picnic" in the nursery home corner.

This is not to denigrate the Montessori approach. Three of my children went to a wonderful Montessori preschool and they were very happy.

But by formalising the 'practical life' activities, they become a chore rather than a delight. That's not to say children don't enjoy them, but you're fighting with one hand tied behind your back.

Why do that to yourself? Especially when everyday life offers everything you need without having to buy or prepare a thing.

The power of meaningful context

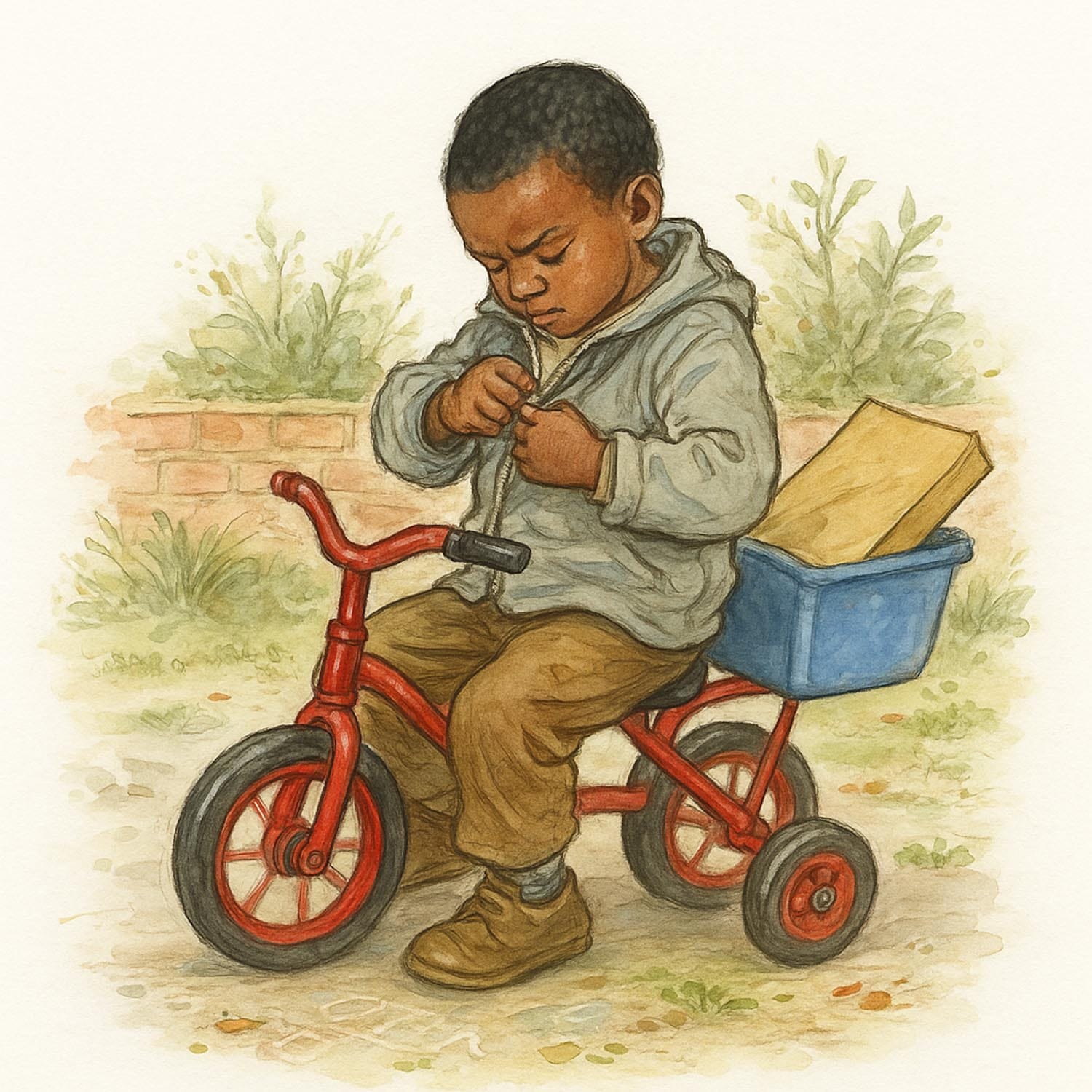

There's another way to make fine motor challenges genuinely compelling: weave them into stories and imaginative play. When children are inhabiting a role - a doctor, a fireman or a receptionist - the fine motor tasks become essential to the narrative, not exercises to complete.

In my teaching days, we'd transform the outdoor home corner (aka the garden shed) into a pizza restaurant. The children would use string phones to take orders, carefully "writing" down requests (usually scribbles, but with determined adult-like concentration). The chef would roll playdough pizza bases and select toppings with careful precision. Finally, and with great urgency, the delivery driver would zip up his jacket before speeding off on the tricycle, bringing hot treats to waiting friends.

This week in Elmwood

What the children are working on - and why it matters

At home, Sam and his mother Rachel are making sandwiches for a picnic. Sam insists on spreading the butter himself, pressing hard with the knife and creating thick, uneven layers. Rachel resists the urge to take over, instead suggesting he try "painting" with lighter strokes.

In the garden, Alice is helping her father repair a broken gate latch. She holds screws steady while he positions the screwdriver, then takes turns trying to tighten them herself. Her movements are still unsteady, but her determination is fierce.

At nursery, George discovers that the water wheel only works when you pour steadily, not in big splashes. He spends twenty minutes perfecting his technique, completely absorbed in the relationship between the subtle adjustments of his hand and the wheel's rotation.

Environmental invitations that build real capability

Rather than setting up "fine motor stations," create authentic opportunities for your child to use her hands purposefully throughout the day.

The kitchen

Open packages, stir batter; pour, sieve and shake. Is there any room in the house that offers more fine motor challenges? Even toddlers can join in, if you don't mind a little clean up. Novice sous chefs will enjoy cutting - and eating - slices of banana with a plastic knife but soon they'll be ready for more. My seven-year-old now knows everything she needs to bake a cake. When the mood takes her, she gets the ingredients down from the cupboard and gets to work. Apart from putting it into the oven, she does it all.

Strategic material placement

A recurring theme in Play with Purpose: make the behaviour you want to entrench the easy and obvious choice:

- Put a craft box on the kitchen table

- Hang coats at child height by the front door

- Leave toothbrushes awaiting a squeeze of toothpaste by the bathroom sink.

- Invite your child to help with chores. Sock must be paired and laundry folded.

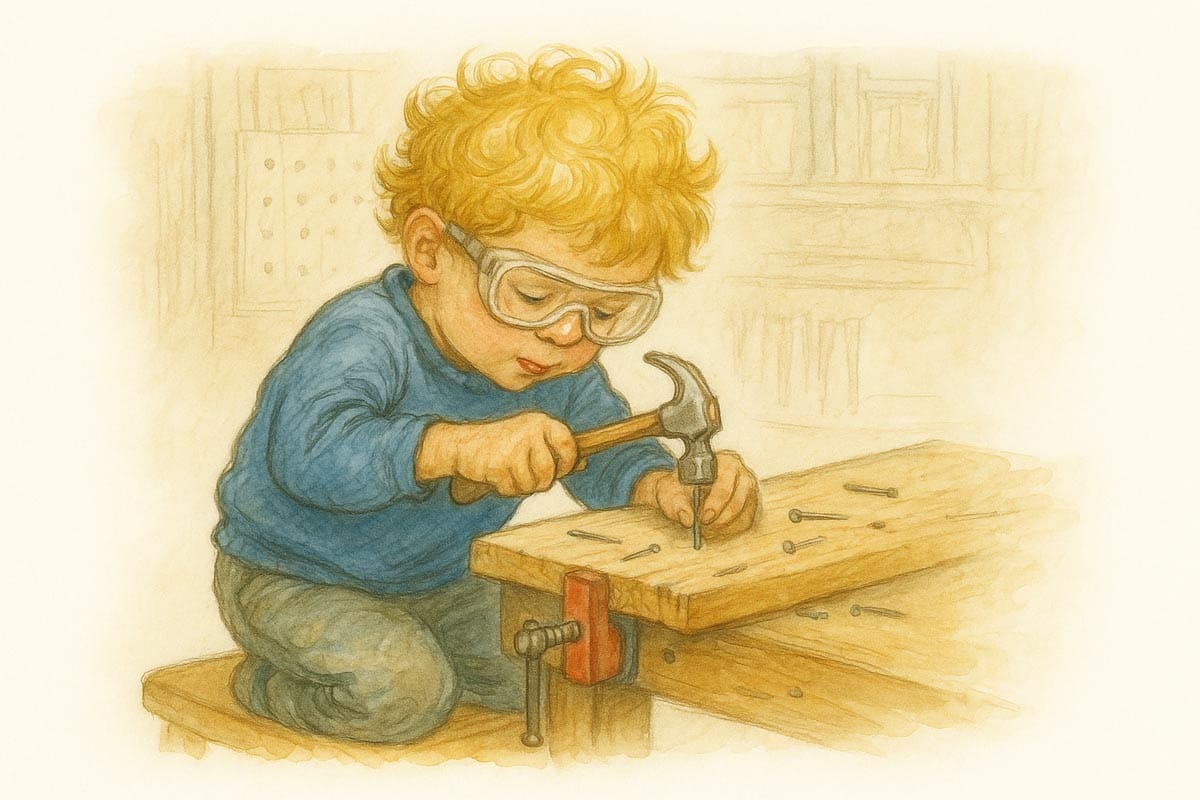

Real tools

No, really.

It's safe (-ish!) and brilliant fun.

And when you're having fun - and can't believe your dad left you alone with the saw - you'll be extra determined to justify his faith in you.

Real tools require more precise movements and provide genuine feedback, like the bite of saw on wood. Toy tools are fine for toddlers but this is Spring to School. We're preschoolers now. We're big.

My own fine-motor workout came from carpentry. I was trusted (possibly foolishly!) with all kinds of tools from a young age. But the cuts, scrapes and occasional hammer-to-thumbnail agony were soon forgotten - and sometimes barely noticed - as I threw myself into day-long projects.

The garden

Provide open-ended materials (tubes, tape, funnels and guttering, for example) and let your child build something meaningful. I once left a similar selection in the garden and, in passing, lamented that the hose wasn't long enough to water the flowers at the back of the garden. It wasn't long before my resident builders were assembling a makeshift waterway to restore life to those wilting plants.

The magic of stationery

Teachers love putting office supplies in the role-play corner because they invite rich, real-world dialogue and play whilst effortlessly incorporating fine motor challenges into the action. Paper clips and staples bind documents, bulldog clips attach paper to clipboards and hole punchers punch tickets for commuters rushing home for supper. The fine motor work happens naturally because it serves the story.

Looking ahead

A year from now, what will your child be able to do? Hold a pencil and write her name with confidence? Fasten her buttons and zip? Unscrew the lid on her favourite drink?

She's sure to get there.

All you have to do is offer a good mix of experiences. Let her try. Let her fail. Let her believe she can do it herself.

Then she will approach writing not as a daunting skill to be learned, but as another interesting way to use her capable hands.

Sam is back at the table with another sheet of stickers, but this time he's completely absorbed in creating a pattern. Each sticker is carefully positioned, edges aligned with mathematical precision.

He easily peels one off, puts it in just the right place and presses it down with satisfaction.

"Look," he says quietly, not seeking praise but simply sharing his achievement. "I made it perfect."

And he has. Not because someone taught him how to use stickers, but because he's had countless opportunities to discover what his hands can do when they're working on something that matters to him.

The mastery was always there, waiting. Sometimes all it takes is the right invitation to reveal it.

Comments ()